Why not everyone is a torturer

Why not everyone is a torturerBy Stephen Reicher and Alex Haslam

Psychologists

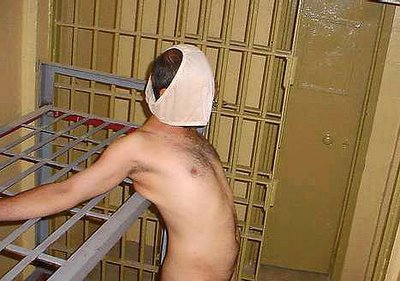

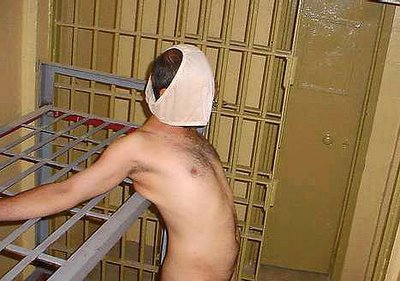

So groups of people in positions of unaccountable power naturally resort to violence, do they? Not according to research conducted in a BBC experiment.The photographs from Abu Ghraib prison showing Americans abusing Iraqi prisoners make us recoil and lead us to distance ourselves from their horror and brutality. Surely those who commit such acts are not like us? Surely the perpetrators must be twisted or disturbed in some way? They must be monsters. We ourselves would never condone or contribute to such events.

Sadly, 50 years of social psychological research indicates that such comforting thoughts are deluded. A series of major studies have shown that even well-adjusted people, when divided into groups and placed in competition against each other, can become abusive and violent.

Most notoriously, the 1971 Stanford prison experiment, conducted by Philip Zimbardo and colleagues, seemingly showed that young students who were assigned to the role of guard quickly became sadistically abusive to the students assigned to the role of prisoners.

Combined with lessons from history, the disturbing implication of such research is that evil is not the preserve of a small minority of exceptional individuals. We all have the capacity to behave in evil ways. This idea was famously developed by Hannah Arendt whose observations of the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, led her to remark that what was most frightening was just how mild and ordinary he looked. His evil was disarmingly banal.

In order to explain events in Iraq, one might go further and conclude that the torturers were victims of circumstances, that they lost their moral compass in the group and did things they would normally abhor. Indeed, using Zimbardo's findings as evidence, this is precisely what some people do conclude. But this is bad psychology and it is bad ethics.

It is bad psychology because it suggests we can explain human behaviour without needing to scrutinize the wider culture in which it is located. It is bad ethics because it absolves everyone from any responsibility for events - the perpetrators, ourselves as constituents of the wider society, and the leaders of that society.

In the situation of Abu Ghraib, some reports have indicated that the guards were following orders from intelligence officers and interrogators in order to soften up the prisoners for interrogation.

If that is true, then clearly the culture in which these soldiers were immersed was one in which they were encouraged to see and treat Iraqis as subhuman. Other army units almost certainly had a very different culture and this provides a second explanation of why some people in some units may have tortured, but others did not.

Grotesque funPerhaps the best evidence that such factors were at play is the fact that the pictures were taken at all. Reminiscent of the postcards that lynch mobs circulated to advertise their activities, the torture was done proudly and with a grotesque sense of fun.

Those in the photos wanted others to know what they had done, presumably believing that the audience would approve. This sense of approval is very important, since there is ample evidence that people are more likely to act on any inclinations to behave in obnoxious ways when they sense - correctly or incorrectly - that they have broader support.

So where did the soldiers in Iraq get that sense from? This takes us to a critical influence on group behaviour: leadership. In the studies, leadership - the way in which experimenters either overtly or tacitly endorsed particular forms of action - was crucial to the way participants behaved.

Thus one reason why the guards in our own research for the BBC did not behave as brutally as those in the Stanford study, was that we did not instruct them to behave in this way.

Zimbardo, in contrast, told his participants: "You can create in the prisoners feelings of boredom, a sense of fear to some degree, you can create a notion of arbitrariness that their life is totally controlled by us, by the system, you, me - and they'll have no privacy.... In general what all this leads to is a sense of powerlessness".

Officers' messagesIn light of this point it is interesting to ask what messages were being provided by fellow and, more critically, senior officers in the units where torture took place? Did those who didn't approve fail to speak out for fear of being seen as weak or disloyal? Did senior officers who knew what was going on turn a blind eye or else simply file away reports of misbehaviour?

All these things happened after the My Lai massacre, and in many ways the responses to an atrocity tell us most about how it can happen in the first place. They tell us how murderers and torturers can begin to believe that they will not be held to account for what they do, or even that their actions are something praiseworthy. The more they perceive that torture has the thumbs up, the more they will give it a thumbs up themselves.

So how do we prevent these kinds of episodes? One answer is to ensure that people are always made aware of their other moral commitments and their accountability to others. Whatever the pressures within their military group, their ties to others must never be broken. Total and secret institutions, where people are isolated from contact with all others are breeding grounds for atrocity. Similarly, there are great dangers in contracting out security functions to private contractors which lack fully developed structures of public accountability.

Power vacuumAnother answer is to look at the culture of our institutions and the role of leaders in framing that culture. Bad leadership can permit torture in two ways. Sometimes leaders can actively promote oppressive values. This is akin to what happened in Zimbardo's study and may be the case in certain military intelligence units. But sometimes leaders can simply fail to promote anything and hence create a vacuum of power.

Our own findings indicated that where such a vacuum exists, people are more likely to accept any clear line of action which is vigorously proposed. Often, then, tyranny follows from powerlessness rather than power. In either case, the failure of leaders to champion clear humane and democratic values is part of the problem.

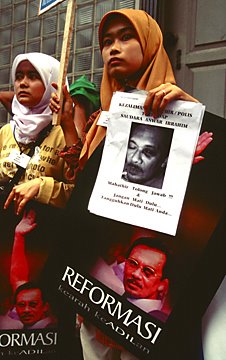

But it is not enough to consider leadership in the military. One must look more widely at the messages and the values provided in the community at large. That means that we must address the anti-Arab and anti-Muslim sentiment in our society. A culture where we have got used to pictures of Iraqi prisoners semi-naked, chained and humiliated can create a climate in which torturers see themselves as heroes rather than villains.

Again, for such a culture to thrive it is not necessary for everyone to embrace such sentiments, it is sufficient simply for those who would oppose them to feel muted and out-of-step with societal norms.

Leaders' languageAnd we must also look at political leadership. When administration officials talk about cleaning out "rats' nests" of Iraqi dissidents, it likens Iraqis to vermin. Note, for example, that just before the Rwandan genocide, Hutu extremists started referring to Tutsi's as "cockroaches".

Such use of language again creates a climate in which perpetrators of atrocity can maintain the illusion that they are nobly doing what others know must be done. The torturers in Iraq may or may not have been following direct orders from their leaders, but they were almost certainly allowed to feel that they were behaving as good followers.

So if we want to understand why torture occurs, it is important to consider the psychology of individuals, of groups, and of society. Groups do indeed affect the behaviour of individuals and can lead them to do things they never anticipated. But how any given group affects our behaviour depends upon the norms and values of that specific group.

Evil can become banal, but so can humanism. The choice is not denied to us by human nature but rests in our own hands. Hence, we need a psychological analysis that addresses the values and beliefs that we, our institutions, and our leaders promote. These create the conditions in which would-be torturers feel either emboldened or unable to act.

We need an analysis that makes us accept rather than avoid our responsibilities. Above all, we need a psychology which does not distance us from torture but which requires us to look closely at the ways in which we and those who lead us are implicated in a society which makes barbarity possible.

(Alex Haslam is a professor of psychology at University of Exeter and editor of the European Journal of Social Psychology. Stephen Reicher is a professor of psychology at University of St Andrews, past editor of the British Journal of Social Psychology and a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.)Story from BBC News at http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/1/hi/magazine/3700209.stmPublished: 2004/05/10 12:57:59 GMT© BBC MMV

Just before I left,

Just before I left,

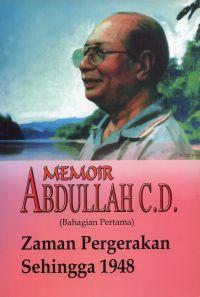

Pak Abu Samah enjoys the distinction of being the first top communist leader who published

Pak Abu Samah enjoys the distinction of being the first top communist leader who published